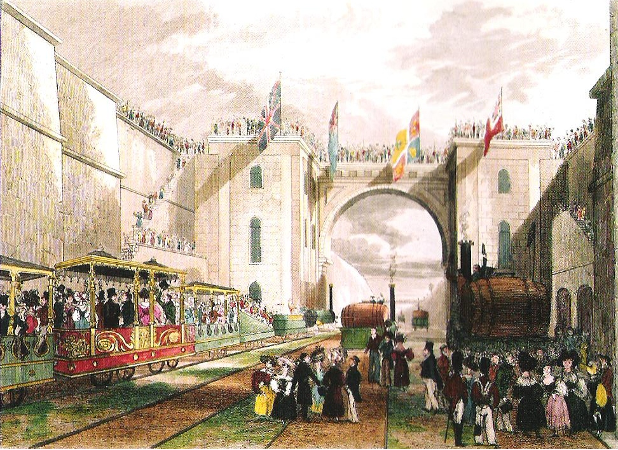

One of the most famous of these took place in England almost two centuries ago, in a distant age when Princess Victoria was still an eleven-year-old girl. When the crowds rushed in for the grand opening of the Liverpool to Manchester railway in 1830, they suspected that something truly novel was at hand. This was, after all, the first passenger train in the world to connect two major cities. The Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, had ventured north for the occasion. The ageing war hero who had changed the course of history at the Battle of Waterloo had come to witness its next chapter.

As the top-hatted and trussed-up passengers climbed aboard the locomotives – previously considered obscure machines for transporting coal – they were at the start of a journey that would eventually encircle the world. The technology was still an utter mystery to most; it must have seemed as if Robert Stephenson and his ilk had tamed a herd of fire-breathing dragons.

Some pioneers feared the human body might even explode at the dizzyingly high speeds – up to thirty miles per hour – that the passengers would reach. In fact, the technology performed immaculately. Yet adjusting to the new world of machines was not easy for all. The prominent MP for Liverpool, the infirm William Huskisson, froze before an oncoming engine and met a horrific end. Despite this unfortunate fatality, the potential of the new technology was staggering. Something astounding had begun.

The energy spread. Railway fever seized the stock market, unleashing successive waves of frenzied speculation and market mania. The great names of the day – from Emily Brontë to Charles Dickens – were caught up in a cycle of manic boom and terrible bust. In December 1849, Charlotte Brontë lamented the financial wreckage after one such collapse, which had ravaged her own investments: “Many – very many are – by the late strange Railway System deprived almost of their daily bread…”

Yet, despite the mania and the tragedy, those pioneering investors were right: the world would never be the same again. Bands of iron connected the globe. The railways revolutionised every aspect of British society – smashing the cost curve downwards, breaking distribution bottlenecks and radically improving economic efficiency.

Even the appalling debacle of the railway bubble led to positive change, accelerating the adoption of the limited liability company. The railway remained a shorthand for sleek modernism and frictionless modernity – a view that lives on today in the anguished debates over the HS2 project.

The depth of the change the railways wrought was not understood at first, just as in our own age we grapple with hazy ideas of how artificial intelligence will change our identities and our world.

Historian Benedict Anderson spoke of nineteenth century nation states as “imagined communities”, where newspapers, official diktat and national emblems served to create a national consciousness for the first time. Before the railways, every town in England had its own time zone, based on local longitude and dating back to time immemorial. Within a few years, all of this was consigned to the dustbin of history. The nation was soon bound together in a single harmonised time zone with the advent of “railway time”.

New technology now began to shape nations. In the words of Marshall McLuhan, “First we build the tools, then they build us”. A process that continues apace in our own age, where through the “world brain” of the internet and our ever-present smartphones, we are all becoming digitally enhanced beings.

Windows into the future continued to open. Over a century later, imagine being a fly on the wall in a seminar in a nondescript San Francisco hotel. It is now December 1968, a year of many revolutions. In a single brilliant exposition, Doug Engelbart from the Stanford Research Institute starts to unveil many of the ground-breaking computer technologies that would shape the decades to come. These include a graphical user interface with windows; the first computer ‘mouse’ in a wooden case, and the ability to follow hypertext links from page to page. History now records this event as the “mother of all demos”. All these revelations were revealed to a select audience as if by magic, decades before they became known to most. It was if the audience had been gifted their own private viewing of the future.

Strange messages continued to arrive, as if from tomorrow. On January 8, 2009, the fortunate few recipients on a cryptographic mailing list received a communication from a mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto, “announcing the first release of Bitcoin, a new electronic cash system.” Embedded in the genesis block of Bitcoin was a quote from the Times of London; “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”. Even as the world remained utterly mired in the turmoil of the global financial crisis, ideas of money and value were continuing to evolve, not without controversy.

Many of us will recall a more recent demonstration event. In 2016, the AI system AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol, the reigning champion at the ancient board game of Go. Starting with no prior knowledge of the game, the computer started to play the game from first principles. Within hours, it was able to achieve a level of skill that took human beings 1,500 years to attain. Then it started to make strategically unprecedented moves – moves that no human had ever imagined. Subsequently, of course, people absorbed these non-human insights into their own play. Industrial age technologies such as the train expanded our physical capabilities. Now our cognitive capacities are being upgraded.

William Gibson’s celebrated observation rings true here; that at any point in time, “The future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed”. We should try and train ourselves to spot those moments in history when the invisible has been made visible. How do we parse the signal from the noise, the hype cycle from the substance, the press release from the true breakthroughs? Perhaps more importantly, we should consider the likely second and third-order social and economic consequence of the trends that are making our world. Instead of asking, ‘when and how will self-aware AI arrive?’, we should perhaps ask: ‘what will this mean for everything and everyone else?’

Alan Kay, doyen of the astonishingly innovative laboratory at Xerox Parc, succinctly opined “The best way to predict the future is to invent it”. Many innovators work backwards from a place of impossibility; a Da Vinci inventing gyrocopters and submarines, a Musk dreaming of terraforming Mars. Hard science fiction has arguably been one of the most influential literary genres in history simply because it has inspired so many real-world innovators.

Perhaps we can also apply this kind of reverse logic to ourselves, in seeking to design our own careers. With every choice, every decision, every breath, we are writing the story of our personal futures. The fact this is a self-development cliché doesn’t make it any less true. Do we occasionally see glimpses of our own possible tomorrows?

Yet very people have a gameplan, one that methodically works back from a defined future goal. It is usually far more comforting – and quite frankly, more interesting – to obsess with the macro issues, with technology and the news cycle, rather to apply future-orientated insights to our own careers.

With reflection, we can all start to discern the contours of our own futures. Intuitively, we often sense which experiences and capabilities we are moving towards, and which ones we must learn to leave behind. Knowing the difference, makes all the difference.

© Paul Darroch Groden 2024. This is not investment, legal, regulatory, or financial advice and is produced for educational purposes only.